Your contacts

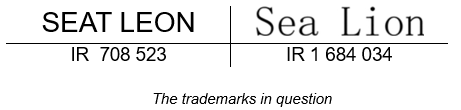

How different do “animal trademarks” need to be to coexist in the Swiss market? This is one of the questions to which the Swiss Federal Administrative Court offers a compelling answer in its recent decision B-4947/2023, resolving a dispute between SEAT S.A.’s trademark “SEAT LEON” and BYD COMPANY LIMITED’s trademark “Sea Lion” (fig.), both registered for vehicles and related components under Class 12.

SEAT S.A. opposed the registration of “Sea Lion”, arguing that it infringed on its established trademark “SEAT LEON”. On the surface, the case seemed straightforward: both marks relate to identical or at least similar goods and contain the letters “SEA” and “L.ON”. Furthermore, the words “Lion” or its Spanish equivalent “LEON” allow reference to strong, evocative imagery. However, the court found that these commonalities did not amount to a likelihood of confusion.

First, the court emphasised that Class 12 goods, motor vehicles and their components, are expensive, durable, and typically purchased with a high level of consumer attention. This significantly lowers the potential for confusion, even where some similarities between trademarks exist.

Then, although “Sea Lion” covered goods related to SEAT S.A.’s offerings, the court focused on the distinctiveness of the marks. It examined the protection granted to the “SEAT LEON” trademark. The court found the distinctiveness of “SEAT LEON” to be average. In fact, while “SEAT” is a well-known car brand in Switzerland, this did not automatically extend enhanced protection to “SEAT LEON” and SEAT S.A.’s attempts to prove broader recognition of the “SEAT LEON” sign on the Swiss market lacked strong evidence, relying mostly on media references and marketing materials (which often referred solely to “SEAT” or to variations such as “SEAT IBIZA”), without substantiated consumer studies or precise, documented sales data. The court completed its analysis by further clarifying that although the well-known character of the sign “SEAT” in Switzerland for land vehicles is notorious, the sign still enjoys only average scope of protection due to its initial narrow scope. Indeed, originally the word “SEAT” could have been understood as the basic English word “seat”, descriptive of a part or function of the products for which protection is claimed. Regarding the “LEON” sign, which has an intrinsic average scope of protection, the court noted that while case law recognises that vehicle trademarks can be notoriously well known in Switzerland, it is not established that specific vehicle models can also achieve a sufficient degree of recognition to be granted a higher level of protection.

The court’s analysis delved further into the phonetic, visual and conceptual aspects of the trademarks. After confirming the existence of visual similarity, the court noted that the notoriety of “SEAT” also influences the pronunciation of and the meaning attributed to the “SEAT LEON” trademark.

Consequently, while acknowledging that both “SEAT LEON” and “Sea Lion” share certain auditory overlaps, the court determined that there is only a distant phonetic similarity between the trademarks in question. This is because in the “SEAT LEON” trademark the relevant public will recognise the “SEAT” motor vehicle trademark and therefore pronounce it as an acronym (rather than as the English word “seat”), while “Sea Lion” will be pronounced as two English words.

Semantically, the court determined that the juxtaposition of “SEAT”, a recognised automotive brand, against “Sea”, a term indisputably tied to marine imagery, created a stark conceptual divide. In fact, according to the court, also the element “LEON” must be analysed in relation to the notoriety of “SEAT”. Consequently, it will be seen as a model designation rather than a core brand element. More so as it is customary for “SEAT” to name its models after Spanish cities, which the attentive consumer will not have failed to notice. In contrast, “Sea Lion” evokes an image unrelated to vehicles. In the said mark the relevant public will see the basic English words “sea” and “lion”, and their combination will be immediately and effortlessly understood throughout the country as a reference to a well-known carnivorous sea animal. Therefore, the court ruled out any conceptual similarity between the two trademarks, because there is none between a car brand and a vehicle model on the one hand, and a sea animal on the other hand. In addition, the court clarified that even the presence of the concept of “lion” in the “SEAT LEON” trademark (“LEON”) would not suffice to establish a conceptual similarity between the signs in question, as it would evoke the animal living in the savannah, a very different animal than the sea lion.

In light of this, the court determined that, in the absence of any thematic analogy, the graphic and remote phonetic similarities were largely offset and confusion could be ruled out in this case in the minds of the attentive target consumers. Consequently, SEAT S.A.’s opposition was dismissed, and the “Sea Lion (fig.)” trademark proceeded to registration under the Madrid Protocol.

This ruling is a powerful reminder that in trademark law, not all creatures are treated equal, especially when sea lions and Spanish horse- or rather lion-power swim in the same legal waters. The decision seems notably strict, given the undeniable visual similarities between the signs and the awareness of the brand (and car model) SEAT (LEON). It emphasises the importance of conceptual differences for Swiss Courts, the necessity of bearing in mind the basic level of English proficiency of the Swiss population despite English not being a national language, and the need to present strong evidence of a brand’s awareness and increased distinctiveness. This is crucial in opposition proceedings, even if you think your trademark is well-known. Convincing Swiss-specific evidence, particularly for the exact product brand and solid sales figures, is essential.